Identifying, analysing, then fixing a failure is the standard troubleshooting scenario.

However, how can you ensure that an intermittent failure is adequately fixed, to prevent undesired consequences?

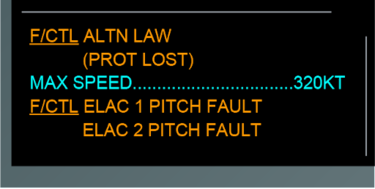

A case of reversion to alternate law

On several successive flights, A320 flight crew noted an ECAM warning F/CTL ELAC 1 PITCH FAULT. They informed the maintenance team who then investigated. However, the fault did not show up during any of the ground checks. The aircraft was systematically released back into service by using ELAC resets and without further troubleshooting.

After several flights, the aircraft experienced a F/CTL ELAC 2 PITCH FAULT which when combined with the latent F/CTL ELAC 1 PITCH FAULT led to the loss of flight control normal law and to a reversion to alternate law* F/CTL ALTN LAW. The crew landed safely, although extra monitoring was required in addition to their standard tasks.

The case above is a typical example of a repetitive failure combined with another single failure leading to more severe consequences on the aircraft systems and handling in flight. Limiting repetitive failures is key to prevent potentially aggravating situations. That is why repetitive failures should not be ignored and require an efficient monitoring process.

* Reversion to alternate law means all protections, except manoeuvre protections, are lost. Refer to FCOM PRO-ABN-F_CTL

Why spotting intermittent repetitive failures can be difficult

An intermittent failure is one that the maintenance team may not confirm on the ground when performing the fault confirmation test from the troubleshooting manual (TSM). This may be because the failure is only triggered during certain flight conditions (flight phase, humidity, temperature, …).

An intermittent failure becomes repetitive if not identified and fixed. The notion of repetition applies to failures that appear on a particular aircraft during the same or on different flights, and not necessarily consecutively. This may be despite maintenance actions being carried out as rectification attempts.

Maintenance teams may be tempted to try to « fix » a failure by resetting computers. However, this may only clear the indication, with the failure remaining latent.

Inappropriate system resets may seem to be a "quick-fix" on the ground to dispatch the aircraft. But they are not consistent with TSM recommendations and are outside the scope of the applicable published Instructions for Continued Airworthiness (ICA). These resets can lead to hidden deteriorating conditions of the system and to unexpected side effects.

More on resets: Safety First article “System Reset: Use with Caution” - July 2021

A320 circuit breakers used for computer reset.

The difficulty also lies in identifying a failure which does not have a set timely pattern. It may keep happening but irregularly, and maybe not even on successive flights.

3 keys to addressing repetitive failures

- Report failures

A failure not recorded by flight crew and not properly investigated by maintenance teams may, over time, combine with other independent failure, leading to a possible NO GO situation or to severe operational consequences.

Any failure should be recorded by the flight crew or the maintenance personnel. This includes:

- failures not monitored by systems, like noises or vibrations, as they will not trigger any ECAM alert or PFR record allowing maintenance to identify a repetition.

- any reset of any computer as repetitive resets could indicate a permanent failure.

Proper reporting associated with an accurate review of maintenance history will allow efficient monitoring for identification of those failures to be considered as repetitive.

2. Adopt an efficient system for monitoring

Setting the thresholds

Depending on regulation and depending on local authorities’ requirements, airlines may be required to put in place a system for detecting and managing repetitive failures in order to fix them as early as possible to ensure safety objectives are met.

The repetition, and the timeframe of repetition are the two main drivers. The key for successful monitoring is to understand where to set the associated threshold. Several factors need to be considered and adapted to the context. Some examples are:

- frequency of the failure compared to the number of flights

- aircraft configuration (MOD embodied, open MMEL items, …)

- affected aircraft systems

- potential spurious indications using CMS filter, TFU, ISI, …

- engineering experience

The monitoring system should be able to cover events occurring over both short and long-term periods. Priority should be given to short-term monitoring to address frequent, repetitive failures and catch them as early as possible. For short-term monitoring, using a rolling-period is recommended as it is continuous and consequently much more accurate.

However, the frequency of intermittent failures may start accelerating over time as the faulty equipment/part condition deteriorates. Long-term monitoring can be beneficial to detect increasing trends earlier, allowing teams to anticipate troubleshooting slots and resources.

Using an adapted monitoring tool

Airbus recommends maintenance teams carry out daily monitoring by using the aircraft data, logbook entries and associated maintenance actions. However, for longer-term monitoring, an adapted tool connected to raw data is a key enabler, such as the Airbus Skywise Health Monitoring (SHM) or a maintenance information system as this will automate the identification of repetitions.

Finally, the monitoring system has to be constantly challenged to confirm the selected monitoring thresholds are still appropriate to identify the targeted repetitions.

This example shows a failure which increased over a long period. A monitoring tool would have identified the trend much earlier.

3. Troubleshoot on the ground

When a fault or a crew observation is reported, the first step of troubleshooting for the maintenance teams is to confirm the failure on the ground by testing the system or reproducing it.

The risk is that, in some instances, intermittent failures might not be confirmed and may be perceived as a spurious or as an isolated case and not further investigated. This risk is even more present if there are time or operational constraints.

In all cases, after three occurrences of a failure, even if it is still not confirmed, the Airbus troubleshooting manual (TSM) recommends applying the fault isolation steps until the failure has been resolved.

An appropriate monitoring also allows detecting an equipment that experiences a similar failure scenario after repeated short service periods, also called a rogue unit. Such parts are likely returned as NFF from the shop. If a failure condition has not been identified and such a part is installed on aircraft, it may contribute to leave latent failure on aircraft.

Refer to AirbusWorld > Content Library > Supplier Support > Contracts > No Fault Found Policies for more information on rogue units and NFF policies.

By strictly conforming to regulations and to published procedures, flight crew and maintenance teams can limit exposure time to repetitive failures - crucial to ensure aircraft safety.

Such failures require specific attention as they are difficult to identify and to troubleshoot.

Airbus recommends flight operations and maintenance teams:

- systematically report occurrences and maintenance actions, including resets

- identify repetitive failures, using appropriate monitoring

- always keep in mind that troubleshooting can start with authorised resets but should not end there. The appropriate troubleshooting actions, recording and proper monitoring should always follow.

Your media contacts

Contact us

Cyril Montoya

Maintenance Safety Enhancement Manager

Jean-François Bourchanin

Expert Operations Flight Controls

Latest FAST articles

Continue Reading

Getting ready for A350 cabin retrofits

Web Story

FAST

The first A350s are reaching eight years in service, and the wave of cabin retrofits which is now starting will rapidly gain momentum over the next few yea

Turbulence alert - The collaborative network

Web Story

FAST

Intermittent repetitive failure

Web Story

FAST

End-of-life Reusing, recycling, rethinking

Web Story

FAST

In-flight health monitoring

Web Story

FAST